Demystifying Knowledge Management for Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Africa

There is absolutely no doubt in the fact

that all over the world, the micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)

sector have been acknowledged for playing major roles in the economic

development of many countries, especially in the so-called first-world nations. SMEs constitute the largest proportion of

businesses and play tremendous roles in employment generation, provision of

goods and services, creating a better standard of living, as well as

contributing significantly to the gross domestic products (GDPs) of all

developed countries (OECD 2000). In this

article, our aim is to simplify the concept of Knowledge Management (KM) to

entrepreneurs, promoters, managers and other stakeholders in the micro, small

and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) sector in Africa. Although the concept of KM has been around

for over a decade, it is still relatively new, still growing and has gained significant

recognition all over the world.

Our focus here is to demystify the

general understanding of the concept of knowledge management and to discuss the

enormous potential benefits awaiting African SMEs who choose to adopt a

‘deliberate’ KM initiative into their overall organizational strategy. We would also examine the symptoms and

crucial need for a KM project, the building blocks of KM, the modes of

knowledge transfer, and provide hands-on tips for SMEs interested in designing

and implementing an effective KM programme within their organizations.

Why the Focus on African SMEs?

Over the last few decades, it has been

observed that despite the enormous potentials of the SMEs sector and its

immense contribution to the economic development of the developed countries,

the performance of the sector still falls short of expectation in many

developing countries especially in Africa

(Arinaitwe, 2006). This has contributed

to further widening the gap between the developed and developing countries,

resulting into more requests for aids, grants and policy formulations in

support of developing countries.

The Africa Growth and Opportunity Act

(AGOA) project of America, Millennium Development goals (MDGs) and other

international trade policies of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) – such as

the policy against trade dumping – are all targeted towards supporting the sustainable

economic development of African countries and stimulating their export

potentials. However, whether or not

African businesses and SMEs choose to take advantage of such policies and

opportunities is entirely up to Africans and not the developed countries.

There is an old adage that says:

“knowledge is power”, and not just knowledge, but “the application of knowledge.” Nevertheless, many managers still wonder why

some businesses tend to succeed and others fail, or why some businesses make

huge profits and others make abysmal losses.

It is neither an issue of size nor capital; it’s more often about how knowledge is being managed within organizations. The question that then comes readily to mind

is: what really is knowledge? Although

there appears to be no single definition for the term knowledge, it still simply refers to the consciousness/awareness

that provides any sort of advantage/benefit over the lack of such

consciousness/awareness.

What is Knowledge Management?

Having looked at a simple definition of

knowledge, what then is Knowledge Management (KM)? On the first sight or hearing of KM, people

readily think it is a fad concerning the introduction of massive computer

systems, very high volumes of data, too much grammar and requires the help of

external consultants, gurus, etc. This

first-timer perception towards KM is worsened by the fact that, just as there

is no universally accepted definition of ‘knowledge’, there is also no single

definition for KM. This does not mean

that some KM initiatives do not involve the use of computer systems or the aid

of experts and external consultants (especially within large organizations),

but our focus here is to understand the central meaning of the concept of KM, its fundamental principles

and how it can be applied to SMEs.

In this light and for the purpose of

this article, we prefer to adopt a simplistic perspective of the concept of KM

in order to aid our understanding for SMEs.

Simply put, the concept of KM refers to how businesses can leverage on

the experiences of their managers, employees, customers, competitors and other

stakeholders, alongside the understanding of their product and service

offerings and the market/business environment.

All these can be used to the organizations’ best advantage, thus

generating greater value (Santosus and Surmacz, 2001).

Putting Knowledge Management to Work

The concept of KM can be better

understood with the aid of analogies, stories and case studies. To give us a better understanding of how the

concept can be utilised in a small to medium-sized enterprise in the African

context, let us examine two case studies. The first case is that of a small-sized

hairdressing salon with the owner and six other employees in Ahoada, Nigeria. The second case is that of an experienced

baker in a medium-sized bakery in Bukoba ,

Tanzania

Case Study 1: The Hairdressing Salon in Ahoada, Nigeria

Consider the case of a professional hair

stylist in Ahoada as a knowledge worker.

She does more than simply braiding and plaiting or washing and styling the hair

of her clients. In the process of beautifying their hairs, or when asked by

clients, the professional stylist would gladly provide useful advice and tips on

how to look after their hair, such as: ‘make sure you use pink oil/conditioner

on your hair each time you re-touch’; ‘don’t carry your braids for too long in

order to prevent your hair from breaking-off’ or ‘XYZ Relaxer is better for

your hair, because it is milder and more gentle on the scalp” and so on. For

such a stylist, accurate advice may lead to generous financial tips at the end

of the hair session. On the other hand, clients who have benefitted from the

tips rendered by the stylist are more likely to use the services of her Salon

again, and possibly introduce their friends to the Salon. Now, if the professional stylist is willing

to share what she knows with other stylists, then all the other stylists could

eventually become more professional, and in the process improving the Salon’s client

base and revenue.

How would a KM initiative make this

happen? The owner of the Salon can decide to reward stylists for sharing their

professional tips with others by offering them incentives. Once the best tips

are gathered, the manager/owner would discuss them with all her stylists. She

can also get the tips typed, printed and distributed to all the stylists. The end result of a well-designed KM initiative

is that everybody benefits: bigger tips, more hair dressing deals and better

professional outlook for stylists. In addition, clients are made to look more

beautiful with better-maintained hairs due to the collective knowledge of

stylists. Furthermore, the Salon owner also wins because there would be repeat

business from satisfied clients, who could even act as a medium of

advertisement to friends and relatives in Ahoada and surrounding towns.

Case Study 2: The Bakery in Bukoba, Tanzania

Conversely, consider the case of an

experienced baker who started working in a bakery at the age of eleven due to

financial constraints from his family to send him to school, so he lacks formal

education. Over the past thirty-five years, he has worked in all sections of

the bakery and is highly skilled at every stage in the production process.

Mtembe Foods Ltd recently took over a medium-sized bakery in Bukoba for bread

production and has engaged the services of this experienced baker. The new

manager of the bakery is finding it difficult to plan the work schedules for

the experienced baker, thereby overloading him with menial work. Moreover, the manager plans to introduce new

varieties into the production line because the experienced baker has little

formal education. Therefore, it is difficult for him to conduct lessons for the

other less experienced employees.

How can KM solve this problem? The manager needs to understand that he can

still get the experienced baker to transfer his knowledge through some other

means. If the baker is willing to share his experience, and if the manager

decides to reward him for sharing, then four other apprentice bakers can be

placed under the experienced baker to shadow his operations, thereby gaining

knowledge through repeated practice of what they see from the experienced

baker. The manager should allow for a flexible work environment that encourages

free-flow of ideas and discussion in the language that everyone understands. This socialisation process is a mode of transferring

tacit knowledge (discussed below). Eventually, the bakery would have improved the

skills of its employees, its production quality and output, and successfully introduced

its new products. Meanwhile, the experienced baker would have been rewarded and

the residents of Bukoba would derive more satisfaction from the new bread

varieties.

A well-designed and implemented KM

programme always produces win-win outcomes to all its stakeholders. The two above case studies are practical

examples of how KM can be used effectively in SMEs. Concisely, two basic

thoughts from the above cases: first, that KM initiatives have to do with

people i.e. it involves the use of human resources/capital; second, management

plays a very crucial leadership role towards ensuring the success of the programme.

Benefits of Adopting a Knowledge Management Initiative

There are vast potential benefits

awaiting African SMEs who choose to adopt a KM initiative as part of their overall

strategy. These benefits include:

·

it

enhances improvement in turnover rate and increases profitability by

facilitating the production of new appropriate products and services suited to

meet the needs of consumers;

·

it

can brings about improvement in an

organisation’s customer service management;

·

it

encourages high employment retention rates by recognising the value of employees’

knowledge and sharing ability;

·

it

streamlines company operations and leads to reduction in costs by eliminating

redundant or unnecessary processes;

·

it

enhances organisational learning and improves the creative abilities within the

organisation;

·

it fosters the free flow of ideas, thereby

stimulating timely product/service development and innovation;

·

it

creates a sense of identity, security, loyalty, responsibility and commitment

in employees since they know the company values them and their contribution

towards its success;

·

it

strategically positions a company and offers readiness for penetrating into new

markets; and

·

it

improved organisational efficiency and effective use of available resources etc.

Symptoms of Knowledge Management Need

In most organisations today, especially in

SMEs, it is not very difficult to identify when a KM initiative is lacking. The

following symptoms below are evident of organisations that need to have KM

initiatives (Shelton, 2006):

1. An organisation where decision making,

is slow due to the absence of one or a few key persons. This is a common trend in many SMEs, where

the absence of the entrepreneur or manager tends to cripple the operations of

the firm;

2. A company where delegation of

responsibilities are frequently, duplicated due to communication gaps;

3. A company where there are high rate of

recurring mistakes;

4. An organisation that lack professional

interpersonal relationship;

5. Where innovation and development

strategy is Top- Bottom, i.e. employees are not motivated to be creative and

initial new ideas;

6. Where consumer relations are strained

and customers tend to complain frequently of being dissatisfied with a product

or services;

7. Where a company competes on only price

and cannot keep up with the market leader in the industry;

8. Where employees do not feel any sense of

loyalty or commitment to the company;

9. Where a company’s rate of launching new

products and services is very slow; and

10. Where customers service processes and technologies,

are understood by only some few employees within the company.

The Crucial Need for a Knowledge Management Initiative: Forms of

Knowledge

Generally, the concept of KM is still a

growing field of management. It has been suggested that many managers

irrespective of the varying sizes of their firms, still do not understand the

principal essence of the concept due of its broadness and its subjectivity to a

range of interpretations by speakers, consultants and writers; making KM uneasy

to be purchased as a service or completed within a year (Orlov, 2004).

Nevertheless, the fundamental need for

KM within an organisation is under-pinned by two key factors. First, more companies are losing their members

of staff due to the on-going recession, budget cut- back resignations,

retirements etc., after spending huge amounts of resources to train and develop

them. This is a challenge for MSMEs, and Delong (2004) noted that in far too

many organisations, knowledge is in the danger of disappearing along with the

employees who acquired it. MSMEs in Africa are the worst hit in this current

economic climate because they lack resources to either pay high salaries, or

execute training and development, thus limiting their capacity to retain their

staff for a long-term agreement. It would also appear to be a waste of scarce

resources for an MSME, if an employee the company has spent money to train and

develop suddenly decides to leave on her/his accord for a bigger/blue chip

company without sharing his/ her knowledge with other staff members.

Second, two broadly identified forms of knowledge,

that is the explicit knowledge, and the tacit knowledge underscore KM. Explicit

knowledge is the codified or hard knowledge as is sometimes referred to, which

remains within the four walls of an organisation at the end of a normal workday

in the form of manuals, regulations, handbooks, information on databases etc.

The tacit or soft knowledge, which leaves the organisation at the end of the day’s

work, i.e. knowledge gained from experience leading to certain intuitions, insights,

and hunches comfortably seated in the heads and minds of employees and other

stakeholders. As such, the crucial need

for a KM initiative and the challenge for a company is to ensure that as tacit

knowledge goes home to sleep or out of the organisation due to retirements,

resignations and in search of other opportunities. There are spare copies stored in

organisational databases, handbooks, manuals and in the heads and minds of

other staff members.

Building Blocks of Knowledge Management: A Basic Framework for

SMEs

For a KM initiative to be effective and

for any organisation to benefit from an effective KM programme, there needs to

be strict adherence to at least one basic framework. Some authors have described this as the

streams of knowledge or the stages of KM. Whatever it is termed, SMEs need to understand

the basic model for designing an effective “tailor-made” KM programme. They are discussed below:

·

Needed

Knowledge: irrespective of the size of any company, the very first stage in

designing a KM initiative is in identifying what knowledge is needed for the

organisation to meet its goals, aims, and objectives. This would require an SME to undertake a

strategic analysis of its industry, and it would involve some form of environmental

scanning, interviews customers, suppliers and other stakeholders. It would also involve some brainstorming and

the development of a number of scenarios of the emerging trends and likely

future occurrences within the industry.

·

Available

Knowledge: after identifying the needed knowledge, the next step is to

determine what knowledge is presently available within the organisation. This would require carrying out an analysis

of the organisation’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT),

core competence and business position.

These analyses would consider issues such as the organisation’s

personnel profiles and experience, understanding of the relevant laws and

regulations, its industry, organisational culture, corporate image, products

and services, customers and other stakeholders.

·

Knowledge

Gap: this is basically the difference between the “Needed Knowledge” and the

“Available Knowledge”. This is a very

salient aspect in the design of a KM programme because a sound insight into the

knowledge gap would help the organisation understand how best to strategically

close up the gap in order to gain competitive advantage.

·

Knowledge

Creation: is the ability to bridge the gap that has been identified within the

organisation knowledge needs. Here,

several techniques of knowledge creation would be used such as researching,

training, and studies into customers buying patterns and satisfaction.

·

Knowledge

Base: after knowledge have been created and developed, there needs to be a systematic

and structured manner through which the knowledge is stored/locked i.e. kept on

board. This involves the creation of a

“knowledge base” whereby knowledge can be determined and made available for

everyone to access. Knowledge bases

could include setting up computer databases, installing internal communication

networks, and keeping project files and other hard or physically accessible

documents.

·

Knowledge

Sharing and Transfer: this is another core aspect of the KM process because

after knowledge have been created and stored, it should be communicated,

transferred and shared amongst employees, between managers and employees, as

well as between departments. This

heavily depends on the structure and culture of the organisation, because it

requires a flat structure and culture that encourages free flow of

communication, mutual knowledge sharing and ensures that the appropriate

knowledge gets to the appropriate person at the appropriate time. Knowledge can be communicated, shared, and

transferred using different techniques. Detail discussions below.

·

Knowledge

Application: is at this stage that “knowledge” is usually referred as “power”. Here, insights from the knowledge created, locked,

and shared can now be strategically utilised to give the organisation a

particular advantage in order to gain a competitive edge within the

industry. This stage forms the principal

element in the knowledge management process and prominently driven by the

management of the organisation.

·

Evaluation

of Applied Knowledge: this stage is also very important in fine-tuning and streamlining

the KM process. Here, an assessment

implementation on the effectiveness of the KM programme and the result

generated from the applied knowledge.

The assessment evaluation is using several techniques such as internal

and external audit, project evaluation, customer, and employees’ satisfaction

and benchmarking. This evaluation forms

a critical part of identifying the new knowledge gap for further improvements;

and the strengths of the KM initiative that can be further maximised and horned

for better competitive advantage.

From the building blocks of KM discussed

above i.e. the Needed Knowledge stage through to the final Evaluation stage,

provides us with an understanding that the KM process is an unending process

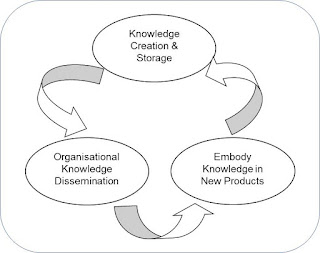

because it drives continuous improvements within the organisation. This process can be broadly categorised into

three phases which can simply be termed as the “Knowledge Management Trilogy”

as represented below:

Figure I: Knowledge Management Trilogy

Modes of Knowledge Transfer, Sharing and Communication

In every organisation, it is the

responsibility of managers to ensure that knowledge created within the

organisation is properly disseminated and utilised. According to Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), the

emphasis here is not on individual knowledge but organisational knowledge,

because if individual knowledge is not shared, it will have very little effect

on the organisational knowledge base. The

onus on managers is therefore to facilitate the sharing, transfer and

communication of knowledge and its movement from one part of the organisation

to another. As mentioned earlier, there

needs to be a knowledge base or lock, where explicit knowledge is collected and

allowed to interact with tacit knowledge.

Again, Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) termed the interaction between the two

forms of knowledge as “knowledge conversion” and their model known as the SECI

4-mode process remains one of the most acceptable models of knowledge

conversion:

A. Socialisation: this refers to the conversion from

tacit to tacit knowledge i.e. converting new tacit knowledge through shared

experiences. Individuals can use new

experiences to recount old ones. This

interaction can be one-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-many e.g. oral reports,

meetings between employees and customers, mentoring of younger employees,

training sessions and getting less experienced employees to shadow more

experienced ones. The case of the

experienced baker in the Bukoba bakery above is a good example of

socialisation.

B. Externalisation: this conversion is from tacit to

explicit knowledge through emails, books and manuals, tapes etc. This can involve the presenting of practical

experiences of employees that can be codified and put into a book form or

computer database for easy access. A

good example of this is the case of the hair stylist in Ahoada discussed above.

C. Combination: this conversion is from explicit to

explicit knowledge through more structured, complex and systematic arrangements

such as the use of computers, intranets, internets, and websites which are

mainly found in large organisations. It

can also be through workshops, seminars, and trainings too for both large

companies and SMEs.

D. Internalisation: this is conversion from explicit to

tacit knowledge and it depends on an individual’s ability to make sense out of

the explicit information. Organisational

libraries and computer applications can help people recognise patterns and aid

their understanding.

Tips for African SMEs on Designing and Implementing an Effective

KM Initiative

1. Entrepreneurs and SME-managers should

firstly understand that every KM programme needs their full and concerted

support to be effective.

2. Strong leadership is very crucial to the

success of any KM initiative. The role

of the entrepreneur or SME manager must shift from being the sole source of

knowledge to managing and networking the stream of information, its uses. Leadership should no longer perch at the top

of the organisation, but at the centre.

This is because true leadership hinges on the ability to grasp the

value-creating potentials within the firm as opposed to having an “I know all”

mentality and handling the whole work load alone (Bukowitz and Williams, 1999).

3. SMEs should imbibe a culture that

encourages the continuous learning and development of all employees and

engenders the ability of “learning to learn” from their experiences and

experiences of others. Periodic training

and development needs to be incorporated into their operational system so that

employees can learn new skills, update their professional knowledge and have

the freedom to creatively play around with new ideas.

4. SME managers should learn to structure a

base within the firm where knowledge can be collected; and then encourage

transfers and sharing of the stored knowledge.

Managers should beware of barriers of knowledge transfers such as

insecurity that brews among employees.

5. Entrepreneurs and managers must have the

sense of duty to reward employees who choose to share their knowledge with

others. This is because when employees

feel they are giving more than what they are getting, it gives them the

opportunity to seek greener pastures where their contributions will be

appreciated better.

6. Since KM is about people and ideas,

entrepreneurs should give employees a sense of identity within the SMEs, their

mission and vision; and also allowing them to learn from mistakes.

7. SMEs should learn to take advantage of

social networks in order to expand their customer base. They should also create strategic alliances

that can help improve their market position.

8. Entrepreneurs and SMEs need to

understand that knowledge management is not a one-off project in the life of a

firm, but a continuous project that helps an organisation to re-invent itself

towards better performance.

It is no longer news that we presently

live in a knowledge-driven world, and it has become clearer that the so-called

‘thin line’ that differentiates business successes from failures is “knowledge”. The central point is in understanding the

knowledge gap, create and store the appropriate knowledge and embody the

knowledge in their products and services.

This is because the slogan for businesses today is gradually becoming

“manage-your-knowledge or die.”

In conclusion, for SMEs operating in

Africa to take advantage of the available opportunities and expand their

business capabilities they need to strategically and effectively initiate KM within

their organisations. I hope you have been able to derive a

better understanding into the world of KM from this article. You too can begin

to think of your own small or medium-sized business in the light of the above

analogies, building blocks and tips; and see what you can put into perspective.

It is salient to mention that the concept of KM is relevant and practicable to

every field of human endeavour and to every strata of the society, from public

to private sector, profit making to non-profit making, religious bodies, and

large to medium, small and micro-sized organisations. Until next time, keep managing your knowledge effectively.

References

·

Bukowitz,

W. R. and Williams, R. L. (1999). Looking Through the Knowledge Glass. CIO

Enterprise Magazine [online] Available from: http://www.cio.com/archive/enterprise/101599-book.html

[Accessed: 02 Feb. 2006]

·

Delong,

D. W. (2004). Lost Knowledge: Confronting the Threat of an Aging Workforce , USA :

Oxford University

·

Nonaka,

I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The

Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of

Innovation. Oxford : Oxford University

·

Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2000), “Small and

Medium-sized Enterprises: local Strength, global reach”, OECD Policy Review,

June, pp.1-8.

·

Orlov,

L. M. (2004). When You Say ‘KM’, What Do You Mean? CIO Enterprise Magazine

[online] Available from: http://www2.cio.com/analyst/report2931.html.

[Accessed: 02 Feb. 2006]

·

Santosus,

M. and Surmacz, J. (2001). ABCs of Knowledge Management, CIO Magazine [Online].

·

Shelton University of

Central England , UK

This piece is a modified version of two

articles earlier published by the author in the Business Connect Newsletter of

the Abuja Enterprise Agency; and later updated and published online in January

2008. The author still considers the subject interesting and relevant, hence

the re-publication on his personal blog. Please be kind enough to leave your comments and feedback.

Comments

Post a Comment